So, I live in Maine. The locals say, quite correctly, that its the way life oughta be. The way we keep massive hordes away from our paradise is to make it kinda chilly 6 months of the year. The fact that I live in a circa 1830 farmhouse is a constant reminder of that.

Last winter I froze a kitchen water pipe in the basement. It was due to a gap in the foundation. I patched up the hole and insulated the pipe. (Oddly I inherited 90% of the water pipes insulated, but not this stretch.) The night it froze was not the coldest of the year (it was probably 20 above the coldest mark), but there was a strong wind and no snow on the ground so the cold air just swept through the gap onto the pipe. The rest of the winter passed without further incident.

I put a thermometer in the vicinity, but frankly the basement is kinda dark and creepy and you don't go venturing into the back in the winter without a reason. So the thermometer wasn't all that useful. The sensible thing to do would be to put a $20 wireless thermometer (e.g.

AcuRite Digital Wireless Weather Thermometer Indoor Outdoor

) down there with the readout in the kitchen.

But why do that, when we could go for geek overkill?

The wireless thermometer has some downsides: the receiver is clutter for something rarely used, I still have to remember to look at it, it has no log and the most interesting data is when I am sleeping, it only measures one place per piece of clutter, it lacks an alarm facility, and it needs batteries that inevitably will die in situ.

Clearly this is a job for a $500 computer instead, right?

It appears this is generally done with a "one-wire" network. 1-wire is a dallas semi standard for simple devices that can be powered and read with one wire. You daisy chain them together, typically using one wire from a piece of cat-5. You really need 2 wires, the second is for ground.

This is really neat stuff. There are sensors for temp, humidity, pressure, and even ground water for your garden. A bunch of places sell this stuff in kits, where the sensors come in a little box with an rj-45 "in" and an "out" if you want to chain another senor off of it. Or you can just buy the sensors for a lot less and solder the leads onto the ground and data wires wherever you want a reading. Each one has a serial number it reports as part of the 1-wire protocol so you can tell them apart, and its pretty easy to auto explore the chain and then power each sensor individually to get a reading (don't read them simultaneously).

The temperature gadgets, completely assembled wirth rj-45 connectors and little cases can run $25 each. But the sensors themselves

are just $4 or less in single quantities. (Buy them by the thousand and you can get them for a buck.) I bought just the sensors.

In addition to the sensors, you also need a driver circuit to drive the power, do the polling, etc. There are several

schematics for building them, but I gave into my

software engineering side and bought a

prebuilt one wire usb interface, for $28.

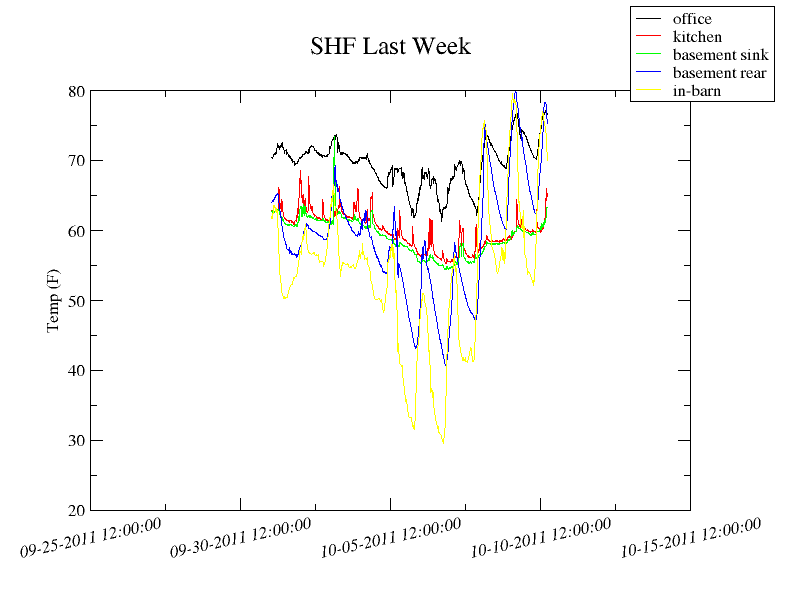

My primary interest is in the basement, but as long as I'm stringing a cable along the rafters I might as well measure a few different points. So I'll grab my office, the basement, the dining room, and the kitchen. I might stick the final sensor outside and cover it in shrinkwrap so there is a "control" number to compare the others to. We are heating this season with a pellet stove instead of central heat, so this information ought to help determine the effectiveness of the various fan placements I'm considering.

Once everything is in place the data can be captured a myriad of ways. The most common are the one wire filesystem, or by using digitemp. (google bait: if digitemp returns CRC errors, clear the configuration file it saves - this cost me hours of resoldering connections that were just fine.) After that

normal linux graphing software can go to town.

I need to order a couple more sensors to layout the final network - I wanted to build a prototype first. It was easy enough.

To do it you'll need: an RJ-11 crimping tool (not rj-45 for ethernet), an rj-11 end. Some cat-5 or cat-3 that is long enough to run your network, and a soldering tool.

The way I wired it, only the middle two wires matter for the crimp. I have blue/white on the left and blue on the right as viewed with the clip down and the contacts away from you. We're going to use white for the signal and blue for the ground. Attach one of the sensors to the end of the cable. The signal pin is the middle one, and the ground pin is on the left. (Left is defined with the flat side of the sensor facing up and the leads pointed down. The right lead is not used, you can trim it off (I've just bent it out of place in this picture).

With the end sensor in place, you can add as many more as you like along the line by just stripping the insulation in place and soldering the leads right onto the cable wherever they need to go. This 1-wire stuff is extremely forgiving of my attempts to pretend that I know what I'm doing with electronics hardware.

Obviously you need to tape up or shrink wrap all the joints, I left them open on the prototype for photos. With this in place,

digitemp -a -r 800 happily reports two different sensors within half a degree of each other. Huzzah!

Now its off to grab the sensors I need for the real thing, installing the cable in the basement along with the other probe points, and getting a graph and alarm server going on the IP network. Such fun!